Scientifically speaking, a “failure” is when a part does not perform as the customer expects, or the part fails an internal test. Failure analysis can be a valuable tool for determining what the next step should be to solve a problem. First, a cost/benefit analysis should be done to determine if the study would be beneficial. If a failure analysis is warranted, there are tests that are usually performed that lead to the most likely mode of failure.

Failures of parts means different things to different people. There are times when the manufacturing process simply does not produce the parts that the customer expects. Sometimes it is not to the print or specification, and other times it is to the print, but it still does not function as the customer thinks it should. Failure analysis can show the failure mode and condition, and can be a very valuable tool for determining what the next step should be to solve the problem. Hopefully, a non-conforming part is caught by internal inspection, but occasionally it will get to a customer.

Customer complaints can be costly, ranging from recalls and line shutdowns to deterioration of a customer relationship, depending on the severity. Some companies have sufficient internal resources to provide data that leads to a solution, but many turn to an independent laboratory or consultant. The engineer or person in charge of handling the problem must be data-driven or the problem will not be solved. In many corporate environments, it is difficult to maintain a balance between the corporate need-to-know and the data available at any one time.

Failure analysis from NSL can help you identify which conditions or components are causing your product to not perform as your customers expect it to. Our failure analysis services can also help you recognize shortcomings in your manufacturing, assembly, inspection, or delivery processes. Then you can use this information to prevent future failures and address the issues as to why your product is defective.

For example, we once worked with a business that created eyeglasses to help them identify why labels weren’t sticking securely to their glass lenses. The labels were sticky enough and the lenses seemed clean, so they hired us to analyze their production process to determine the cause of the issue. After studying every aspect of their process, from material procurement to inspection, we determined the cause of the failure. One of their employees would always chew gum while constructing the glasses, and the microscopic particles from her saliva would land on the lenses, which was what was causing the failure. This is a great example of how the reason for a failure is not always obvious.

The experts in our failure analysis lab can help you determine several different kinds of issues that may be leading to a product failure, such as:

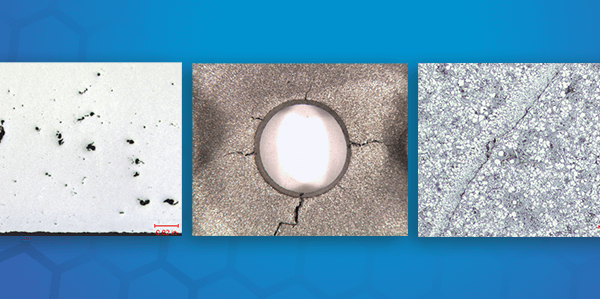

Typical tensiles with grain starting to show.

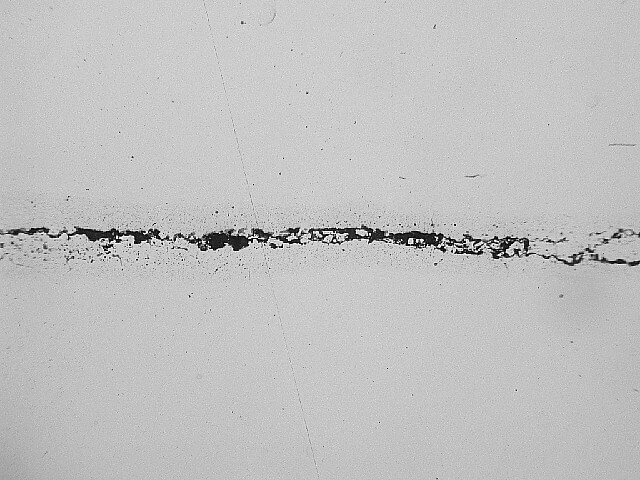

Oxidized crack – metallography.

In the next post of our Failure Analysis blog series, we will explain the different things you should consider before performing a failure analysis. To be notified when the next blog post is published, simply contact us to subscribe to our e-mail list.

Metal additive manufacturing has improved productivity by orders